News Story

Digging Deeper: Forensic Engineering

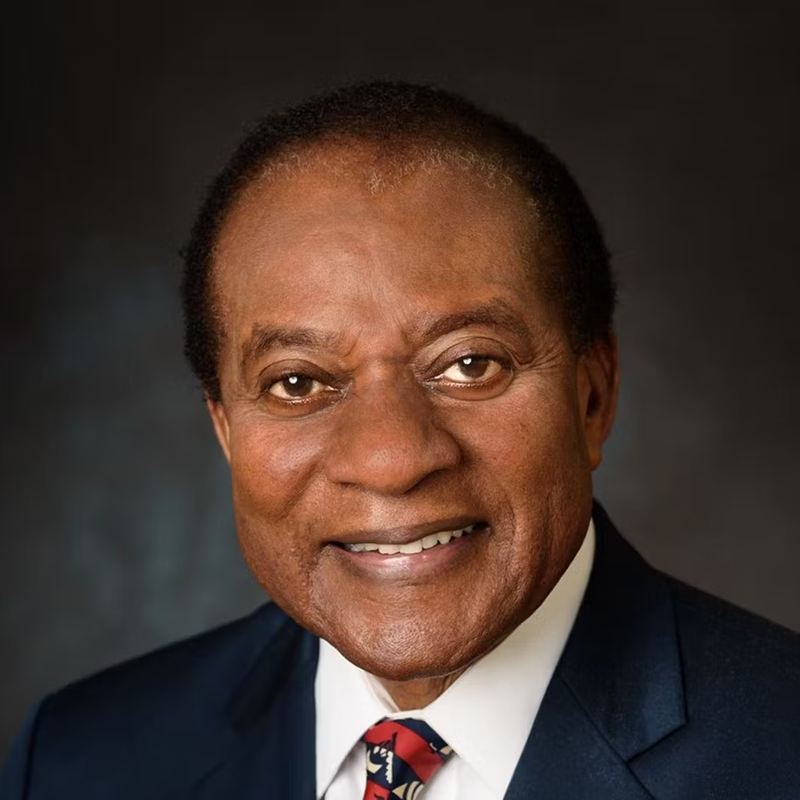

Time and again, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering adjunct professor and alumnus Kenneth O’Connell (B.S. ’81, M.S. ’82, Ph.D. ’91) echoes a mantra made famous by Bill Gates: “It’s fine to celebrate success but it is more important to heed the lessons of failure.”

As president of O’Connell & Lawrence, Inc., a multidisciplinary engineering and consulting firm based in Olney, Md., O’Connell has seen firsthand how engineers serve a critical role in uncovering the hows and whys behind project failures to equip project managers with lessons learned moving forward.

Many such men and women work in the realm of forensic engineering – the “application of engineering principles to the investigation of failures or other performance problems,” according to the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

To those unfamiliar with the field, the word “forensic” may call to mind scenes from popular crime investigation television shows; but, according to O’Connell, a forensic engineer’s role can be most accurately condensed into one word: “expert.”

“What best prepares [an engineer] for forensic engineering is a lot of experience,” O’Connell said, noting that acquiring a degree is only the first step. “What a person needs to do is go out and practice engineering and develop his or her craft for 10 or 12 or 15 years to acquire the expertise needed to become a forensic engineer.”

This holds true largely because forensic engineers take on varied challenges and roles ranging from investigative work to involvement in court proceedings, O’Connell said.

“Sometimes, we get involved with a project while it is still in progress and we have an opportunity to identify and correct problems that have surfaced,” he said. “And then, sometimes, we are brought into projects long after they are done – even years after – and asked to identify what went wrong. In these cases, we are looking for what happened, why it happened, what went wrong and, sometimes, who is responsible for the mistakes.”

Recognizing this, O’Connell & Lawrence employs architects, civil surveyors, construction professionals, project managers, and other area experts who are well-positioned to analyze both in-progress projects at risk of failure and completed projects in which a failure has occurred. Even more, their findings directly benefit public safety by serving to ensure that past mistakes are never repeated.

“Following some of the larger cases involving failures there have been changes made to codes to improve public safety,” said Donald Vannoy, CEE Professor Emeritus, and principal of Trident Engineering Associates, Inc., a forensic engineering business based in Annapolis, Md., Trident boasts a team of engineers across nearly all disciplines, including civil and environmental engineering, mechanical engineering, aerospace engineering, and fire protection engineering.

Along with the company’s forensic, accounting and business valuation experts, all of Trident’s engineers support subrogation and litigation activities, Vannoy said.

“Studying the cases of failures can be valuable to the education process,” he said. “These instances of failure and non-performance provide information that can make a positive impact on human life.”

Although experts from all disciplines of engineering have worked in forensic engineering, from the perspective of a civil engineer, there are specific characteristics that define a project failure, Vannoy said.

“Failure is an unacceptable difference between expected and observed performance,” he said. “It includes total collapse, as well as serviceability problems such as distress, excessive deformations, and premature deterioration of materials. Not all failures are news-making catastrophic failures. In fact, most investigations deal with in-service problems such as deteriorated parking decks, bulging exterior walls, and cracked concrete walls.”

For many forensic engineers, the responsibilities associated with identifying a project failure are twofold. First, the engineer must analyze what went wrong such that the appropriate corrective – or even litigious – measures are taken. Second, the engineer has an inherent responsibility to help clients avoid such mistakes down the road.

“If forensic engineering is looking at failures, what then can you learn from those instances?” O’Connell asked. “I think that’s such an important step in engineering – to take the time to identify what we are learning when things don’t go right. There are a lot of opportunities when something doesn’t go the right way with materials, contracts, or how someone approaches a project. I think sophisticated project owners and the good engineers and contractors learn from their mistakes and improve their craft because of them.”

Although so much of the work done at O’Connell & Lawrence involves investigating and analyzing project failures, the thing O’Connell loves most about his job might not coincide with what is best for business.

“My favorite aspect of what we do is what we call ‘claims avoidance,’” he said. “We train both owners and contractors involved in construction on how to avoid litigation. That’s where the lessons learned really come into play… when we conduct seminars and training sessions and basically say, ‘Here’s how you can do things to prevent having to hire us.’”

In this and many other ways, a forensic engineer often takes on an educator role, O’Connell noted.

“One of the responsibilities of a forensic engineer – especially when you become involved with a court proceeding – is to be instructive,” O’Connell said. “It is your job to convey what happened, and that sometimes means explaining complicated technical or contractual issues or construction processes to non-technical people like lawyers, judges, juries, or arbitration panels. Your responsibility is, ultimately, to be impartial and to apply the engineering knowledge, survey knowledge, or construction materials knowledge you have to determine exactly what went wrong and who’s responsible.”

Doing so often presents a communication challenge, but O’Connell and his colleagues employ a variety of useful methods to convey their findings ranging from PowerPoint presentations and formalized reports to animated timelines and the construction of scale models.

Nevertheless, for both O’Connell and Vannoy, their work as forensic engineers has helped them develop the skills needed to serve as educators for the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and vice versa.

“In forensic engineering, often we’re faced with the task of explaining the technical elements of an engineering project to people who don’t do what we do every day,” O’Connell said. “Sometimes, trying to explain a very complicated problem to an audience that doesn’t have that technical background can be a big challenge – but, that’s also what makes life as a forensic engineer very interesting.”

In the classroom, both Vannoy and O’Connell have provided countless students with a first look at life as a forensic engineer – a career route many still consider nontraditional, despite its growing popularity.

Beginning in the 1990s, Vannoy taught a CEE graduate-level course in forensic engineering, which covered the application of the art and science of engineering in the jurisprudence system. The course addressed topics such as the investigation of the physical causes of accidents and other sources of claims and litigation, preparation of engineering reports, testimony at hearings and trials in administrative or judicial proceedings, and the rendition of advisory opinions to assist the resolution of disputes affecting life and property.

Once a student who first learned about forensic engineering as an undergraduate in Vannoy’s class, O’Connell now teaches both graduate and undergraduate courses in scheduling.

And, while courses in forensic engineering serve to pique student interest in the field, there are a number of reasons the field continues to grow, O’Connell said.

“In some ways, the reasons [for the growth of forensic engineering] are unfortunate because they represent an outgrowth of litigiousness in our society and industry,” he said. “There is unfortunately a lot of litigation in construction and engineering, and in industry in general. Also, there is the forensic side of projects in which engineers are brought in to identify and develop solutions to problems while the project is in progress. I think that need will always be there. Dollar values of projects go up, contracts get more complicated, the risks get more complicated, and people are trying to build projects faster and faster while using more sophisticated materials. All of this contributes to a need for forensic engineers.”

As such, both O’Connell & Lawrence and Trident have established a long list of local, national and even international projects for which the firms have provided forensic support. Collectively, their client list includes the U.S. Army, Department of Commerce, Department of Justice, U.S. Postal Service, the Maryland State Highway Administration and countless other public and private entities.

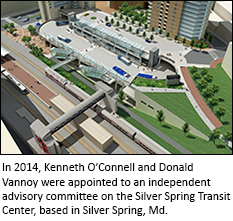

In 2014, both O’Connell and Vannoy were appointed to an independent advisory committee on the Silver Spring Transit Center (SSTC), based in Silver Spring, Md. Together with Norman Augustine, retired chairman and CEO of the Lockheed Martin Corporation and current member of the University System of Maryland Board of Regents, and Algynon Collymore, construction supervisor for DC Water, O’Connell and Vannoy helped issue a report on the project’s shortcomings and potential solutions. The experience provided them with opportunities to hone their investigational skills, handle media inquiries, and give back to their home state through their service.

“We take pride in the work we do for Maryland,” O’Connell said. “That’s home to us, and we’re pretty proud of our ability to help our own state.”

As in the case with the SSTC project, forensic engineers often find themselves taking on different roles. After all, it is not unusual for reporters to field questions to forensic engineers working on high-profile cases. Even more, it is important for forensic engineers to develop the skills needed to properly document any investigational work or evidence collected.

“One of the challenges of forensic engineering is the process of documenting the case by photographs, video and other means,” Vannoy said. “Other challenges include collecting and preserving evidence, analyzing the event, and determining what were the major contributing factors in the collapse or non-performance of the item under investigation.”

“It’s all about having that desire to do investigation work,” O’Connell said. “There are certain people who have a knack for that, or a real desire to do investigations, and that is important because some of it can be tedious. A lot of engineers just want to be out on a construction project building things, and the investigation work doesn’t interest them so much. But, for those of us drawn to forensic engineering, it’s all about finding solutions to the puzzles we encounter.”

And, in doing so, forensic engineers can help resolve project failures or shortcomings, which in turn benefits whole communities, O’Connell said.

“Whenever we can apply what we’ve learned and have a client benefit from that and not end up in a failure situation – not end up in court, but instead, fix whatever is going wrong in a project – that’s my favorite aspect of this line of work,” he said. “That’s when people win.”

Published September 2, 2015